Aesthetic and Symbolic Uncanniness

This photographer that made this image is Eihoh Hosoe and the man making the horns is Tatsumi Hijikata. The image is taken from a larger narrative of images that makes up a book called Kamaitachi.

The Kamaitachi was a mythical weasel creature that moved at lightning speed and cut the legs of farmers as they worked the fields. Others believe it was the vacuum created by a dust devil that would cut the farmer. Over the course of three years, Hosoe and Hijikata created an evocative narrative focused around the person moving from the city to the country-side. And as they moved they swept into the country-side like two Kamaitachi’s, producing images that were uncanny and evocative.

Hijikata in the book, which is comprised entirely of images is supposed to be a Kamaitachi and the representation of the post WW2 Japanese man’s mindset, confused and obliterated after having Western ideology destroy much of the country’s imperialistic cultural mindset. As Hijikata descends upon a remote village he slices open the world and the lives of the people and landscape around him like a Kamaitachi and through Butoh style dancing and expressive acting he exposes his and Hosoe’s views of life post WW2 realized in a contradictory state in rural Japan. Hijikata hides in fields, runs like the wind and acts with the locals. Sometimes they don’t see him as he watches them from rooftops or in sheds, other times he hides alone in the dark crying. Interspersed are images of Hijikata involved in sexual with young Japanese girls. Eventually, we lose track of what or who Hijikata is in the story. All we have to go on are the short explanations and texts from Hosoe and the editors of the book; we are left with the rest.

The photos become uncanny and surreal because of the evocative nature of Hijikata’s actions and Hosoe ability to capture an image at the moment when Hijikata transforms into the Kamaitachi. In Butoh, the actor does not pretend or act like the thing in mind, he or she becomes the thing and lets it out naturally, they don’t suspend their objecthood or hide behind it, they become it entirely. When Hijikata became the Kamaitachi, he was the mythical creature, and in turn, was able to use the Kamaitachi’s characteristics to showcase the modern japanese mindset. As the viewer studies Hijikata’s facial expressions and bodily contortions we feel uneasy and something sinister. We think he is a mad man in some images and other he looks like someone who has not grown out of the age of three. Words can’t always describe what is felt in Hosoe’s images because in addition to Hijikata’s odd and slightly sinister actions, Hosoe’s style of shooting itself is theatrical and slightly warping. If we are to assume that there is a more documentary style of image taking, where the tones are unmanipulated and the angle the image is shot than Hosoe is the antithetical documentarian. He uses varying contrast in his book, selective lighting, his angles feel fluid as if he moves his body with Hijikata’s and other times he frames Hijikata so other details from the rural landscape creep in.

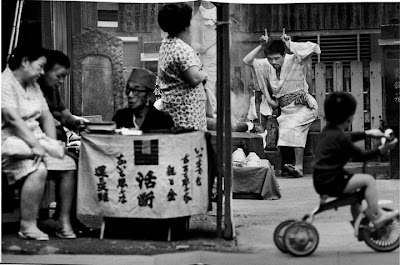

The selected image of Hijikata on the street in a small Japanese village exemplifies uncanniness, which is ever present in the book, because it leaves us with unanswered questions. The image is not a composite, Hijikata really did do this in front of all of these people, he immersed himself and became the Kamaitachi unflinchingly in front of everyone. His face gives off a sinister look and attracts our attention and he makes a set of horns with his hands. He arches his body forward like he might charge. A woman looks at him and so does a child, and this creates a relationship between the three of them. The feeling of something sinister might happen because the boy on the trike gives us the feeling that he is vulnerable to the sinister Hijikata. Yet, the most important part is, no one else gives him any attention. We want to know why? Is it that they do not care, have concern with him, or is it symbolic of the rural person state to not give head to the modern mad man’s state. Hosoe’s hand is also felt and is present within the image, where his camera becomes the true stage for Hijikata’s performance. He selectively frames Hijikata, so that a triangulation is formed between the woman, Hijikata and the boy on the trike, so our attention is drawn to the sinister actor. He then tones this image so that the important details have highlight while the more important forms, such as the silhouette of the boy produce directional lines. (For me, the graininess of the image feels raw, just like the intended purpose of the story).

Hosoe’s 1969 image is uncanny for me because there is the suspension between the real and unreal. The image is not a composite, so I know the event happened and it has familiarity to me. However, the events and stylistic photo techniques of the image give me a feeling that something isn’t right and something wrong is or may happen. And further yet, the text that accompanies the book, which the image is in, makes me even want to search more for answers that I have trouble seeing. Finally, the known symbology of the image itself feels not entirely straightforward, this is really hard for me to state.

No comments:

Post a Comment